Antwan Horfee

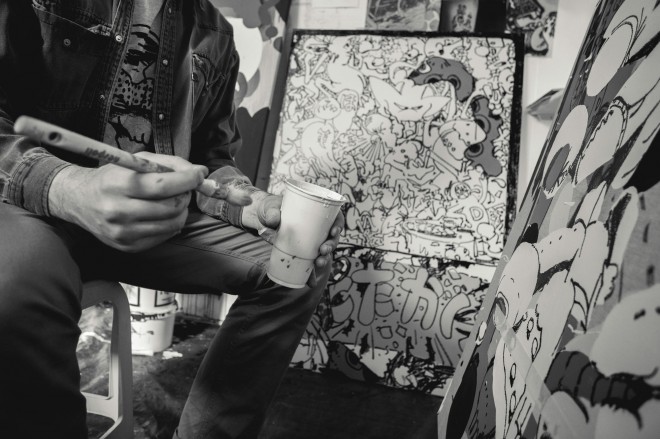

Horfee’s artistic past straddles both the official and the illicit. He studied at the school of fine arts in his hometown of Paris and he painted graffiti. Seamlessly moving between media, Horfee’s style is inspired by everything from European abstract painting to homemade tattoos, vintage animations and underground comics. Whether completing a piece in public outside or painting on canvas or sculpting, Horfee retains a signature style marked by powerful, vibrant color and loose edges. Proudly displaying their flaws instead of hiding them, Horfee’s works neatly blur boundaries between street culture and the restrictions of fine art.

With Traditional Occupations, his first show with Ruttkowski;68 gallery, Horfee challenges the power of prevailing standards. Where do they come from and why do we adhere to them instead of defining new ones? Even structures springing from subversive cultures eventually go mainstream. Whether we should accept them or re-interpret them into a contemporary revolt is a question of personal approach, one that surely depends on the extent to which we are occupied by tradition.

We met the French artist during the preparations of his show and discussed both its title and meaning.

Wertical: Does the exhibition title Traditional Occupations allude to a personal feeling?

Antwan Horfee: Yes. I have always been curious about the rhythm of everyday life; how I create mine and what others do with theirs: work, private time, hobbies, life in the private spaces, things that are only done intimately, things that accompany everyday life. I feel like a voyeur observing how I, myself and other people organize their lives. With this exhibition, I am trying to expose in what respect, everything I do, is my everyday research. So traditional occupations can occur in the cerebral as well as in the physical world.

WE: All spheres of life are somehow occupied by traditions. What exactly do you express with Traditional Occupations?

AH: The exhibition is a pure product of my intimate occupations that I have these days. Thus, I am showing that you can learn from every moment and experience.

WE: What tradition do you personally feel occupied by?

AH: Mainly by the gridlocked notion of our perception. When we think of something, we immediately have an according image in mind. So my occupation is the proximity of the idea and the shape it takes.

WE: How does this express?

AH: In the way that I miss the forest for the trees. I quarrel with deciding what to do next.

WE: Have you find a way to overcome this occupation?

AH: In my opinion, it’s always better to do exploration with a lamp. What I want to say is that you always need a mentor, teacher, professional to learn from his or her good and bad experience to go on yourself. Once the, let’s say, learning process is done, you can move on. So I am constantly challenging myself to try new things and after learning the new thing, I have high expectations on myself: I want the final outcome to be the best I could do.

WE: Thus, you get occupied by traditions to improve them.

AH: That’s true but improvement doesn’t necessarily mean perfection. It is indeed riddled with failures. I think they naturally go with it and I even like them especially in art. I like to see the process of a painting, the different layers that constitute the final work,…

WE: German philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin once said: „Past things have futurity.“

AH: I absolutely agree. Every moment of the now is a piece of the old new. Every moment is made to learn. Your body and brain shouldn’t stock information from the past. This would mean they are made for nothing and thus, a waste of time. Instead, information should be transformed to somewhat useful and inspiring.

WE: Traditions can be both reassuring but also stifling exploration of the uncommon or the new. You obviously pull the positive out of it.

AH: While I also have to confess that I have once thought I don’t need any traditions. I thought I could jump into any river without knowing to swim. Taking the biggest risk becomes a way of doing something, too. The solutions to survive become a technique but I am not fond of using it anymore.

WE: Do you currently see any subversive cultures shaping up? Which ones?

AH: In times of the Internet and New Media, there are even many mini subversive cultures. The sad thing is that all autonomic cultures existing, thanks to its passionate participants, die by the time brands are coming into the game using the cultures to boost up their images. For that, they get involved, took what they needed to raise their cash flow and finally left leaving some leftover they couldn’t make use of. So in my opinion, it’s important to be able to resist and remain independent within the passions.

WE: Are you maybe part of a growing subversive culture yourself?

AH: I am doing many things and always try to listen to what attracts me and why. Graffiti is the subversive culture I am part of. It only exists thanks to the people doing it and still believing in it.

WE: But graffiti is also one of these subversive cultures that is long since used, sometimes even misused, by brands benefiting from it. Is graffiti still a subversive culture after all?

AH: Yes and no. It is actually divided into two parts. The one still aligns to its subversive origins.The other one is indeed established and accompanied by books, documentaries, let’s say, easy access to it.

WE: It’s an important first step to realize in what way we can benefit from traditions. How have you become clear about this?

AH: At one point I started to compare life to a pyramid. If considering the top of it as the end of life, you will eventually have a certain arrangement of ‘stones’ to look back at. But for me, it’s not the height of the pyramid that’s crucial. You will just consume your life if you build up the pyramid too fast. I am literally trying to build on each stone of the pyramid in order to benefit from it.

Current exhibition, ‚Traditional Occupations‘

Archive

- Dezember 2016 (1)

- Oktober 2016 (3)

- September 2016 (24)

- Juli 2016 (20)

- Juni 2016 (24)

- Mai 2016 (18)

- April 2016 (18)

- März 2016 (21)

- Februar 2016 (11)

- Januar 2016 (20)

- Dezember 2015 (20)

- November 2015 (37)

- Oktober 2015 (30)

- September 2015 (24)

- August 2015 (4)

- Juli 2015 (30)

- Juni 2015 (9)

- Mai 2015 (17)

- April 2015 (23)

- März 2015 (18)

- Januar 2015 (8)

- Dezember 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (3)

- Oktober 2014 (10)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (2)

- Juli 2014 (3)

- Juni 2014 (2)

- Mai 2014 (5)

- April 2014 (11)

- März 2014 (12)

- Februar 2014 (13)

- Januar 2014 (10)

- Dezember 2013 (5)

- November 2013 (13)

- Oktober 2013 (24)

- September 2013 (18)

- August 2013 (26)

- Juli 2013 (13)

- Juni 2013 (35)

- Mai 2013 (44)

- April 2013 (49)

- März 2013 (61)

- Februar 2013 (54)

- Januar 2013 (46)

- Dezember 2012 (50)

- November 2012 (58)

- Oktober 2012 (62)

- September 2012 (61)

- August 2012 (63)

- Juli 2012 (64)

- Juni 2012 (61)

- Mai 2012 (63)

- April 2012 (51)

- März 2012 (67)

- Februar 2012 (37)