‚Pioneers of the Comic Strip. A Different Avant-Garde‘

Frankfurt on the Main

Humor, humanity and politics – comic strips convey many aspects of our society. Often regarded as children’s amusement, the visual narratives are in fact much more than that. Frankfurt-based Schirn Kunsthalle proves this with a new exhibition entitled Pioneers of the Comic Strip. A Different Avant-Garde. The six presented artists from the early 20th century show a variety and complexity of works with clear Surrealist, Dadaist, or Pop Art components decades ahead of these artistic movements.

We have had the chance to talk to Dr. Alexander Braun, the curator of the exhibition, and gain insights into the emergence, evolution and artistic components of this specific artistic genre.

WE: When did comic strips appear?

AB: At the beginning of the 19th century paper demand raised rapidly caused by faster and faster printing machines. Paper at that time was made out of cotton and, even though the printing companies were buying old cotton clothes from Europe, paper was constantly missing. In the mid-19th century, a new manufacturing technique made it possible to produce paper from wood. This method allowed the printing companies to produce as much paper as required. Only one newspaper in New York at the end of the century was able to reach up to one and a half million readers every day. If you take into consideration how many newspapers there were in New York and on the whole East and West Coast, it becomes evident that the newspaper was the first mass media read by millions of people all over the United States every day.

WE: Talking fundamental elements; what makes a comic strip?

AB: The now familiar comic books first appeared in the late 1930s. Early comic strips appeared at the beginning of the 20th century when resourceful publishers included magazine supplements in the Sunday edition of their papers in order to distinguish themselves from the competition—the first one was Joseph Pulitzer (1847–1911). These supplements included large comic strips printed in color. The weekday editions soon contained black and white so called ‘daily strips’ with only one line of panels. A central element of comic strips is the typical speech balloons, indicating direct speech.

WE: When did comic strips turn from visual stories in newspapers to works of art?

AB: They were artworks since the beginning. But as in every artistic medium, it is a question of quality: is it a good or a bad comic strip, song, book or artwork? 90% is crap and perhaps 10% is good. Many comic strips did and still do not convey any avant-garde or innovative aspects. Yet the six artists presented in the exhibition do.

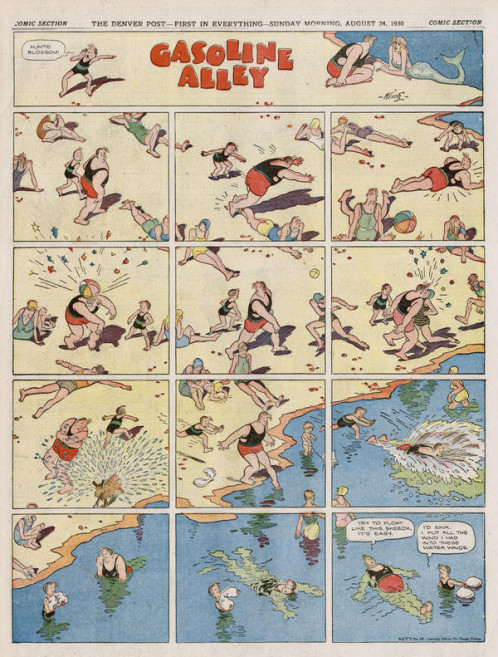

Frank King, for example, invented narration in real time for the comic strip. Skeezix, the main character of his comic, a baby born in 1921, is growing up in a typical neighbourhood of these days. Over 40 years, the reader can follow the life of Skeezix learning to walk, falling in love, combatting in World War II, becoming a father. King depicted a high level of identification in between the narration and the real life.

WE: What is Pioneers of the Comic Strip. A Different Avant-Garde about?

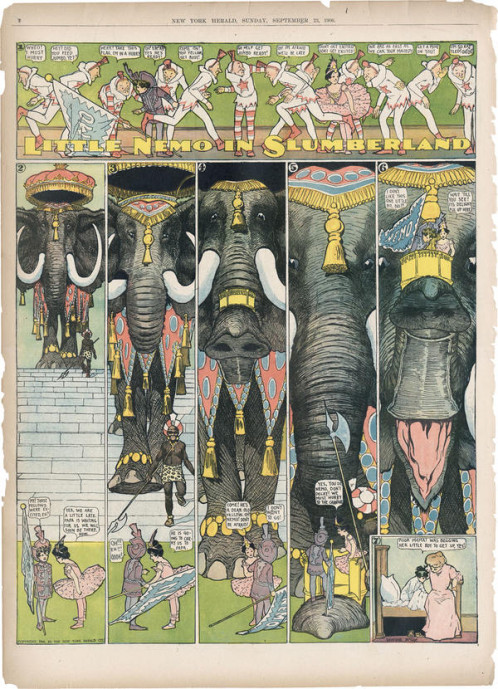

AB: We show six outstanding comic artists who set in six different ways the artistic and content-related standards of the early comic strips. Winsor McCay for example was the first surrealist of the 20th century. He started his strip Dream of the Rarebit Friend in 1904, then Little Nemo in Slumberland, 4 years after the publication of Sigmund Freud’s Traumdeutung but years before the Surrealists published their Manifesto in 1924. His comics have the same features as Salvador Dalì’s and Magritte’s works of art. The animals’ legs are elongated; the faces are so soft that they can be blown away. Yet many of the readers are not aware of how innovative these comic strips are.

WE: And did the artists realize their own innovations?

AB: The comic artists did not consider themselves as artists. The circumstances of their artistic practice made them feel like craftsmen. Most of the original early ink on paper drawings are lost today. After giving the originals to the publisher for printing the comic artists often did not get them back.

WE: Even though humoristic, comic strips often reveal a critical under layer. To which extend are comic strips politically involved?

AB: It depends on the artist and his political engagement. One sequence by Winsor McCay depicts Little Nemo travelling to Planet Mars. The planet belongs to a unique capitalist leader so that the inhabitants of Mars have to pay in order to get the allowance to speak and breathe. The architecture of their houses has a similarity with the ones in Fritz Lang’s movie Metropolis 17 years later. All of these details are a critical depiction of the capitalist society as well as a critic of McCay’s own situation as a comic strip illustrator. At that time, he was very unhappy with his publisher and his personal lack of artistic freedom. Another example is George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. Herriman was very much engaged in the Native Americans’ situation in the reserve areas. Therefore, in one of his comics we can see a Navarro house with the name ‘Calamities’ written on it as a critic of the way Native Americans were treated.

WE: Comic strips or ‘sequential art’ as Will Eisner calls it begun their journey as very popular narratives, what is their role nowadays in our society?

AB: Comics are still regarded as entertainment But there is also an growing understanding of the artistic quality of this genre, especially in terms of graphic novels. With our exhibition in the Schirn Kunsthalle, which presents comic strips in a classic art setting, we hope to open the reception patterns of our visitors to see comic with the same respect (as) art.

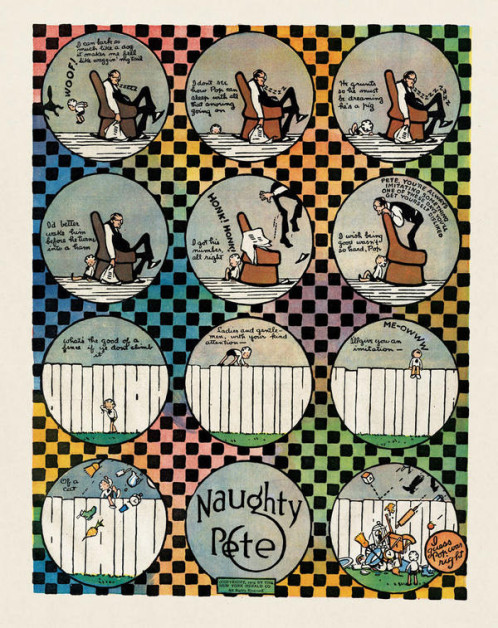

Charles Forbell, Naughty Pete, The New York Herald, October 19, 1913.

Winsor McCay, Little Nemo in Slumberland, The New York Herald, September 23, 1906.

Frank King, Gasoline Alley, The Denver Post, August 24, 1930.

Römerberg

60311 Frankfurt

Germany

Archive

- Dezember 2016 (1)

- Oktober 2016 (3)

- September 2016 (24)

- Juli 2016 (20)

- Juni 2016 (24)

- Mai 2016 (18)

- April 2016 (18)

- März 2016 (21)

- Februar 2016 (11)

- Januar 2016 (20)

- Dezember 2015 (20)

- November 2015 (37)

- Oktober 2015 (30)

- September 2015 (24)

- August 2015 (4)

- Juli 2015 (30)

- Juni 2015 (9)

- Mai 2015 (17)

- April 2015 (23)

- März 2015 (18)

- Januar 2015 (8)

- Dezember 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (3)

- Oktober 2014 (10)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (2)

- Juli 2014 (3)

- Juni 2014 (2)

- Mai 2014 (5)

- April 2014 (11)

- März 2014 (12)

- Februar 2014 (13)

- Januar 2014 (10)

- Dezember 2013 (5)

- November 2013 (13)

- Oktober 2013 (24)

- September 2013 (18)

- August 2013 (26)

- Juli 2013 (13)

- Juni 2013 (35)

- Mai 2013 (44)

- April 2013 (49)

- März 2013 (61)

- Februar 2013 (54)

- Januar 2013 (46)

- Dezember 2012 (50)

- November 2012 (58)

- Oktober 2012 (62)

- September 2012 (61)

- August 2012 (63)

- Juli 2012 (64)

- Juni 2012 (61)

- Mai 2012 (63)

- April 2012 (51)

- März 2012 (67)

- Februar 2012 (37)