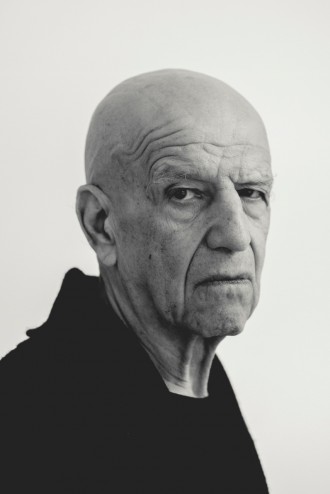

Alex Katz

In the early 1960s, there were only a few people in the world of art who appreciated the works of American portrait painter Alex Katz. At the time, abstract expressionism was more the fashion. Katz’s large-scale, flat paintings were regarded as too simple. Today, he is known as one of the pioneers of Pop Art. The 87-year-old artist still paints and presents exhibitions in galleries and museums around the world. He is always joined by his wife and muse, Ada.

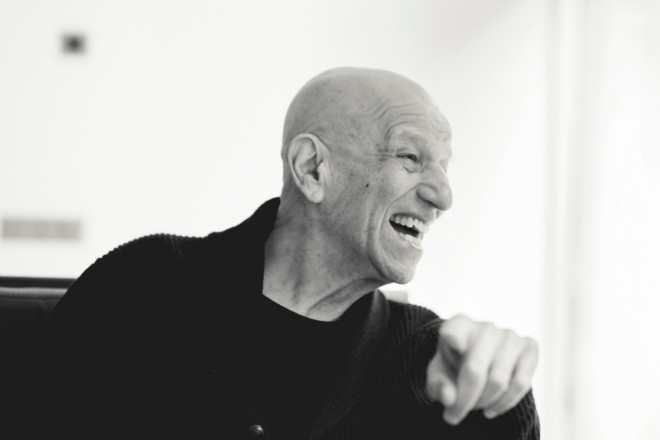

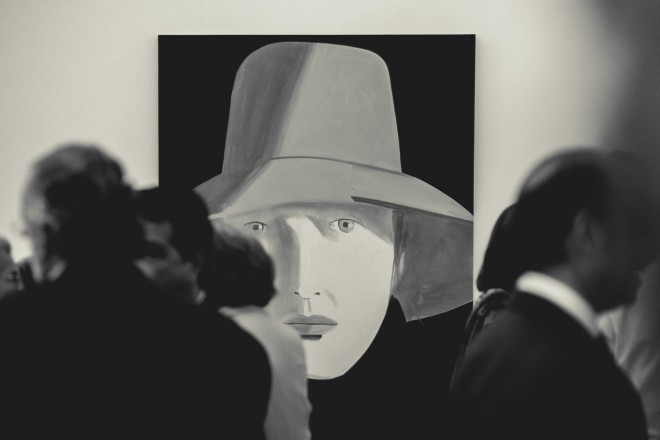

We met Alex and Ada Katz in Spain, where the couple was visiting Katz’s solo exhibition, Red Hat, at Galería Javier López. We talked about the early days of his career, which included forays into fashion and modelling.

Wertical: You are best known for your portraits that appear ‚simple‘ but yet are so intriguing. How do you work? Do your sitters sit before you for hours?

Alex Katz: They only sit for the sketch – the first thing. And then I work on my own. I enlarge the sketch, transfer it with little holes and brown pigments and then draw it with a brush and correct it again and again.

WE: So it’s a direct copy that’s also filled in with your imagination…

AK: Yes, my process passes through different stages – from conscious to unconscious. When I make a drawing, that’s kind of conscious. When I paint, it’s unconscious. It just happens. So I don’t think about. I just do it. It’s the same as riding a bicycle: once you know how to do it, you know it.

WE: Do you tell your sitters how to position themselves?

AK: No, they even move while sitting for me. Because if you hold the present still, you will end up with a still life. And I don’t want to paint a still life. I want to paint a portrait. And I developed my own technique. So they can talk and move while I paint. Actually, all the things that I bring together in one painting are collected from different moments. I could be painting their eyes even as they look around.

WE: Do you have a close relationship to your sitters?

AK: Not all of them. It’s also not too important for my work. I don’t want to tell about the person themselves, but rather what the person appears to be and what they stand for, what they communicate about the moment. I am trying to get a time period straight.

WE: That’s definitely something you manage to do. Your paintings indeed convey the zeitgeist of the time they were painted at. That’s very interesting. Especially for historians. But you once said, painters are the audience you appreciate the most.

AK: Yes.

WE: Why?

AK: Because you see different things in my paintings when you are a painter yourself. I mean the technical things. Paintings generally have five audiences. And they all see something very different.

WE: In what way?

AK: The painter sees it the way it’s painted; a dealer sees something he can sell; a museum person sees something he or she can preserve and put in a museum; a writer sees something he can write about and an innocent person sees a picture.

WE: Are you aware of all these different viewers while painting and do you perhaps try to please them all?

AK: Oh no, I try to focus on my painting to capture what is in front of me. I don’t think that any artist can control five audiences.

WE: But people today are maybe more aware of communicating themselves as marketing tools.

AK: Yes, but these people usually put their emphasis on collectors. There have always been people whose primary motivation is getting people to buy.

WE: What was your primary thing?

AK: I didn’t think too much about it, I just painted. Maybe I would have painted differently had I thought in this direction. But I didn’t. Consequently, I didn’t function very well commercially. I had five shows and they were failures – at least commercial failures. I was painting at the time of abstract expressionism. And I was painting realistic paintings that looked new. I was separate from all the traditional realist painters. They thought my paintings were unfinished and not very notable. And I was separate from the abstract expressionist who considered me as somewhat minor.

WE: Because it’s the simplicity that you first see when looking at your paintings?

AK: Yes, a lot of people thought I was just stupid. My paintings were simple, so they were regarded as simple-minded.

WE: Your portraits mostly show women. What fascinates you about women?

AK: It’s an idea of beauty. An abstract idea of beauty. Most people have some beauty in them. Not necessarily a perfect one, but there is beauty.

WE: Inner beauty?

AK: No, just the face – the physiognomy. It’s pleasing and I think I have always liked it. I used to draw in the subway. I had to learn how to draw.

WE: When was that?

AK: When I went to Cooper Union. It’s a very hard school to get into and my background was not good. But I got in. I think mostly because of my intellect. I personally found I couldn’t draw at all. I could do still life painting but I couldn’t do live drawing. After twenty minutes in front of a white piece of paper, I maybe just managed to draw two lines. So I started to learn it. Whenever I wasn’t talking to someone, I was drawing. I did that for two years to draw on the subways. I looked at all the faces and they all seemed beautiful somehow. Different kinds of beauty.

WE: Aside from the sitter’s physiognomy and attitude, the clothes they are wearing can also speak volumes. In what way are you interested in fashion?

AK: I have always been interested in fashion. One reason is that what’s in fashion represents the present, and that’s what the paintings are. And I have always been fascinated by fashion – the wave of things. It’s like art in the sense that things don’t get better. There is no progress. They say there is progress, but that’s wrong thinking. And that’s the same with modern art. Modern art is based on the premise that there is progress in art. But in fact, art just changes and fashion just changes. There is no progress in fashion – the hem goes up, the hem goes down. The hair is long, then we have enough of long hair, then women need to wear it short.

WE: So your sitters probably wear just what they want. Or do you style them?

AK: No, they just wear what they wear. And that’s so interesting. People find themselves through clothes. And in America, social definitions are created through clothes and haircut more so than money.

WE: You even collaborated with some fashion magazines.

AK: Yes, and I even modelled. I did four, five advertisements.

WE: For what brands?

AK: I did one for Barney’s, for example. And another one for a watch brand.

WE: How did this come about?

AK: I was asked during an opening of an exhibition.

WE: Speaking of photos, do you never used photos as a foundation?

AK: Sometimes. But then again, I get people to pose like you would for a photograph. One year, for example, I decided to photograph people on the beach.

WE: So in the end, you had a photo and a painting – two media depicting the same scene.

AK: There are things that the camera can do and I can’t. And there are things I can do and the camera can’t. Basically, what you consider as realistic is defined by the culture you live in. And the culture we are living in is photographic – photos, camera, TVs – that dominates our vision. A photograph is always a little past tense, it’s always a little behind. A painting can be present tense, respectively – more on point. With my paintings, I go between what you see and what you know.

Archive

- Dezember 2016 (1)

- Oktober 2016 (3)

- September 2016 (24)

- Juli 2016 (20)

- Juni 2016 (24)

- Mai 2016 (18)

- April 2016 (18)

- März 2016 (21)

- Februar 2016 (11)

- Januar 2016 (20)

- Dezember 2015 (20)

- November 2015 (37)

- Oktober 2015 (30)

- September 2015 (24)

- August 2015 (4)

- Juli 2015 (30)

- Juni 2015 (9)

- Mai 2015 (17)

- April 2015 (23)

- März 2015 (18)

- Januar 2015 (8)

- Dezember 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (3)

- Oktober 2014 (10)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (2)

- Juli 2014 (3)

- Juni 2014 (2)

- Mai 2014 (5)

- April 2014 (11)

- März 2014 (12)

- Februar 2014 (13)

- Januar 2014 (10)

- Dezember 2013 (5)

- November 2013 (13)

- Oktober 2013 (24)

- September 2013 (18)

- August 2013 (26)

- Juli 2013 (13)

- Juni 2013 (35)

- Mai 2013 (44)

- April 2013 (49)

- März 2013 (61)

- Februar 2013 (54)

- Januar 2013 (46)

- Dezember 2012 (50)

- November 2012 (58)

- Oktober 2012 (62)

- September 2012 (61)

- August 2012 (63)

- Juli 2012 (64)

- Juni 2012 (61)

- Mai 2012 (63)

- April 2012 (51)

- März 2012 (67)

- Februar 2012 (37)